31 Projection & residual

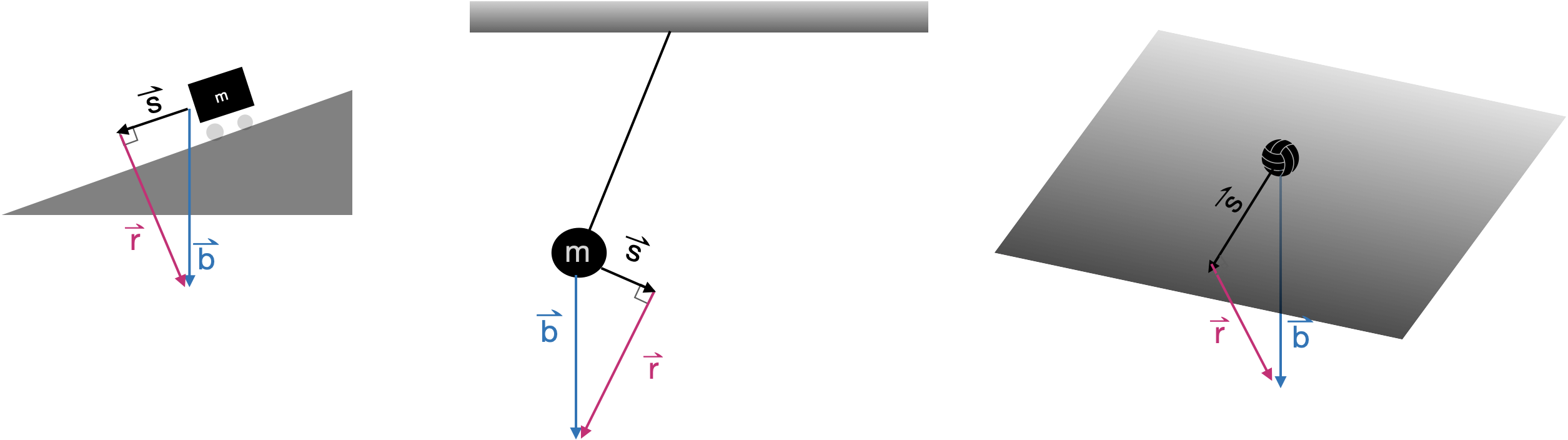

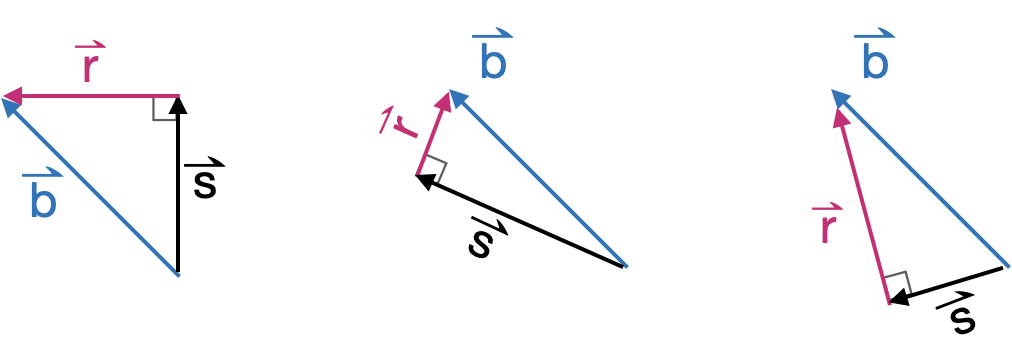

Many problems in physics and engineering involve the task of decomposing a vector \(\vec{b}\) into two perpendicular component vectors \(\hat{b}\) and \(\vec{r}\), such that \(\hat{b} + \vec{r} = \vec{b}\) and \(\hat{b} \cdot \vec{r} = 0\). There are infinite ways to accomplish such a decomposition, one for each way or orienting \(\hat{b}\) relative to \(\vec{b}\). Figure 31.1 shows a few examples.

The hat-shaped crown in \(\hat{b}\), pronounced “b-hat,” often appears in statistics and machine learning. The hat indicates that the quantity is an estimate made from data.

The above example shows just one way the task of vector decomposition arises. Our particular interest in this part of the book is in a more general task: finding how to take a linear combination of the columns of a matrix \(\mathit{A}\) to make the best approximation to a given vector \(\vec{b}\). This abstract problem is pertinent to many real-world tasks: finding a linear combination of functions to match a relationship laid out in data, constructing statistical models such as those found in machine learning, and effortlessly solving sets of simultaneous linear equations with any number of equations, and any number of unknowns.

31.1 Projection terminology

In a typical vector decomposition task, the setting determines the relevant direction or subspace. The decomposition is accomplished by projecting the vector onto that direction or subspace. The word “projection” may bring to mind the casting of shadows on a screen in the same manner as an old-fashioned slide projector or movie projector. The light source and focusing lens generate parallel rays that arrive perpendicular to the screen. A movie screen is two-dimensional, a subspace defined by two vectors. Imagining those two vectors to be collected into matrix \(\mathit{A}\), the idea is to decompose \(\vec{b}\) into a component that lies in the subspace defined by \(\mathit{A}\) and another component that is perpendicular to the screen. That perpendicular component is what we have been calling \(\vec{r}\) while the vector \(\hat{b}\) is the projection of \(\vec{b}\) onto the screen. To make it easier to keep track of the various roles played by \(\vec{b}\), \(\hat{b}\), \(\vec{r}\), and \(\mathit{A}\), we will give these vectors English-language names. 1

- \(\vec{b}\) the target vector

- \(\hat{b}\) the model vector

- \(\vec{r}\) the residual vector

- \(\mathit{A}\) the model space (or “model subspace”)

Projection is the process of finding, from all the vectors in the model subspace, the particular vector \(\hat{b}\) that is as close as possible to the target vector \(\vec{b}\). To state things another way: projection is the process of finding the model vector that makes the residual vector as short as possible.

31.2 Projection onto a single vector

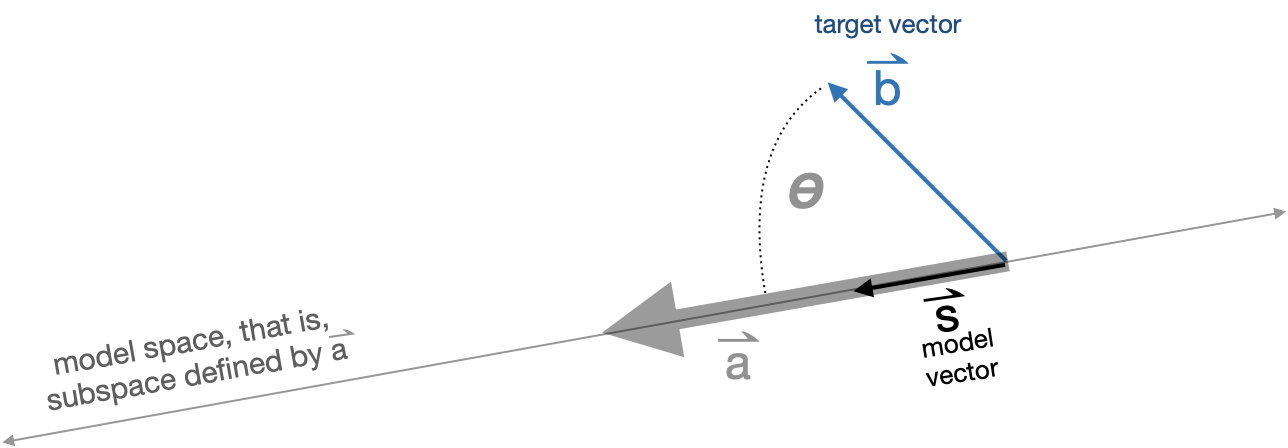

As we said, projection involves a vector \(\vec{b}\) and a matrix \(\mathit{A}\) that defines the model space. We will start with the simplest case, where \(\mathit{A}\) has only one column. That column is, of course, a vector. We will call that vector \(\vec{a}\), so the projection problem is to project \(\vec{b}\) onto the subspace spanned by \(\vec{a}\).

Figure 31.4 diagrams the situation of projecting the target vector \(\vec{b}\) onto the model space \(\vec{a}\).

The angle between \(\vec{a}\) and \(\vec{b}\) is labelled \(\theta\). Section 29.5 shows how to calculate an angle such as \(\theta\) from \(\vec{b}\) and \(\vec{a}\) with a dot product:

\[\cos(\theta) = \frac{\vec{b} \bullet \vec{a}}{\len{b}\, \len{a}}\ .\] Knowing \(\theta\) and \(\len{b}\), you can calculate the length of the model vector \(\hat{b}\): \[\len{s} = \len{b} \cos(\theta) = \vec{b} \bullet \vec{a} / \len{a}\ .\]

Scaling \(\vec{a}\) by \(\len{a}\) would produce a vector oriented in the model subspace, but it would have the wrong length: length \(\len{a} \len{s}\). So we need to divide \(\vec{a}\) by \(\len{a}\) to get a unit length vector oriented along \(\vec{a}\):

\[\text{model vector:}\ \ \hat{b} = \left[\vec{b} \bullet \vec{a}\right] \,\vec{a} / {\len{a}^2} = \frac{\vec{b} \bullet \vec{a}}{\vec{a} \bullet \vec{a}}\ \vec{a}.\] .

31.3 Projection onto a set of vectors

As we have just seen, projecting a target \(\vec{b}\) onto a single vector is a matter of arithmetic. Now we will expand the technique to project the target vector \(\vec{b}\) onto multiple vectors collected into a matrix \(\mathit{A}\). Whereas Section 31.2 used trigonometry to find the component of \(\vec{b}\) aligned with the single vector \(\vec{a}\), now we have to deal with multiple vectors at the same time. The result will be the component of \(\vec{b}\) aligned with the subspace sponsored by \(\mathit{A}\).

In one situation, projection is easy: when the vectors in \(\mathit{A}\) are mutually orthogonal. In this situation, carry out several one-vector-at-a-time projections: \[ \vec{p_1} \equiv \modeledby{\vec{b}}{\vec{v_1}}\ \ \ \ \ \vec{p_2} \equiv \modeledby{\vec{b}}{\vec{v_2}}\ \ \ \ \ \vec{p_3} \equiv \modeledby{\vec{b}}{\vec{v_3}}\ \ \ \ \ \text{and so on}\] The projection of \(\vec{b}\) onto \(\mathit{A}\) will be the sum \(\vec{p_1} + \vec{p2} + \vec{p3}\).

31.4 A becomes Q

Now that we have a satisfactory method for projecting \(\vec{b}\) onto a matrix \(\mathit{A}\) consisting of mutually orthogonal vectors, we need to develop a method for the projection when the vectors in \(\mathit{A}\) are not mutually orthogonal. The big picture here is that we will construct a new matrix \(\mathit{Q}\) that spans the same space as \(\mathit{A}\) but whose vectors are mutually orthogonal. We will construct \(\mathit{Q}\) out of linear combinations of the vectors in \(\mathit{A}\), so we can be sure that \(span(\mathit{Q}) = span(\mathit{A})\).

We introduce the process with an example involving vectors in a 4-dimensional space. \(\mathit{A}\) will be a matrix with two columns, \(\vec{v_1}\) and \(\vec{v_2}\). Here is the setup for the example vectors and model matrix:

We start the construction of the \(\mathit{Q}\) matrix by pulling in the first vector in \(\mathit{A}\). We will call that vector \(\vec{q_1}\)

The next \(\mathit{Q}\) vector will be constructed to be perpendicular to \(\vec{q_1}\) but still in the subspace spanned by \(\left[{\Large\strut}\vec{v_1}\ \ \vec{v_2}\right]\). We can guarantee this will be the case by making the \(\mathit{Q}\) vector entirely as a linear combination of \(\vec{v_1}\) and \(\vec{v_2}\).

Since \(\vec{q_1}\) and \(\vec{q_2}\) are orthogonal and define the same subspace as \(\mathit{A}\), we can construct the projection of \(\vec{b}\) onto \(\vec{A}\) by adding up the projections of \(\vec{b}\) onto the individual vectors in \(\mathit{Q}\), like this:

To confirm that this calculation of \(\widehat{\strut b}\) is correct, construct the residual vector and show that it is perpendicular to every vector in \(\mathit{Q}\) (and therefore in \(\mathit{A}\), which spans the same space).

Note that we defined \(\vec{r} = \vec{b} - \widehat{\strut b}\), so it is guaranteed that \(\vec{r} + \widehat{\strut b}\) will equal \(\vec{b}\).

This process can be extended to any number of vectors in \(\mathit{A}\). Here is the algorithm for constructing \(\mathit{Q}\):

- Take the first vector from \(\mathit{A}\) and call it \(\vec{q_1}\).

- Take the second vector from \(\mathit{A}\) and find the residual from projecting it onto \(\vec{q_1}\). This residual will be \(\vec{q_2}\). At this point, the matrix \(\left[\strut \vec{q_1}, \ \ \vec{q_2}\right]\) consists of mutually orthogonal vectors.

- Take the third vector from \(\mathit{A}\) and project it onto \(\left[\strut \vec{q_1}, \ \ \vec{q_2}\right]\). We can do this because we already have an algorithm for projecting a vector onto a matrix with mutually orthogonal columns. Call the residual from this projection \(\mathit{q_3}\). It will be orthogonal to the vectors in \(\left[\strut \vec{q_1}, \ \ \vec{q_2}\right]\), so all three of the q vectors we’ve created are mutually orthogonal.

- Continue onward, taking the next vector in \(\mathit{A}\), projecting it onto the q-vectors already assembled, and finding the residual from that projection.

- Repeat step (iv) until all the vectors in \(\mathit{A}\) have been handled.

The motivation for these names will become apparent in later chapters.↩︎