Chapter 13 The Logic of Hypothesis Testing

Extraordinary claims demand extraordinary evidence. - Carl Sagan (1934-1996), astronomer

The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function. - F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896-1940), novelist

A hypothesis test is a standard format for assessing statistical evidence. It is ubiquitous in scientific literature, most often appearing in the form of statements of statistical significance and notations like “p < 0.01” that pepper scientific journals.

Hypothesis testing involves a substantial technical vocabulary: null hypotheses, alternative hypotheses, test statistics, significance, power, p-values, and so on. The last section of this chapter lists the terms and gives definitions.

The technical aspects of hypothesis testing arise because it is a highly formal and quite artificial way of reasoning. This isn’t a criticism. Hypothesis testing is this way because the “natural” forms of reasoning are inappropriate. To illustrate why, consider an example.

13.1 Example: Ups and downs in the stock market

The stock market’s ups and downs are reported each working day. Some people make money by investing in the market, some people lose. Is there reason to believe that there is a trend in the market that goes beyond the random-seeming daily ups and downs?

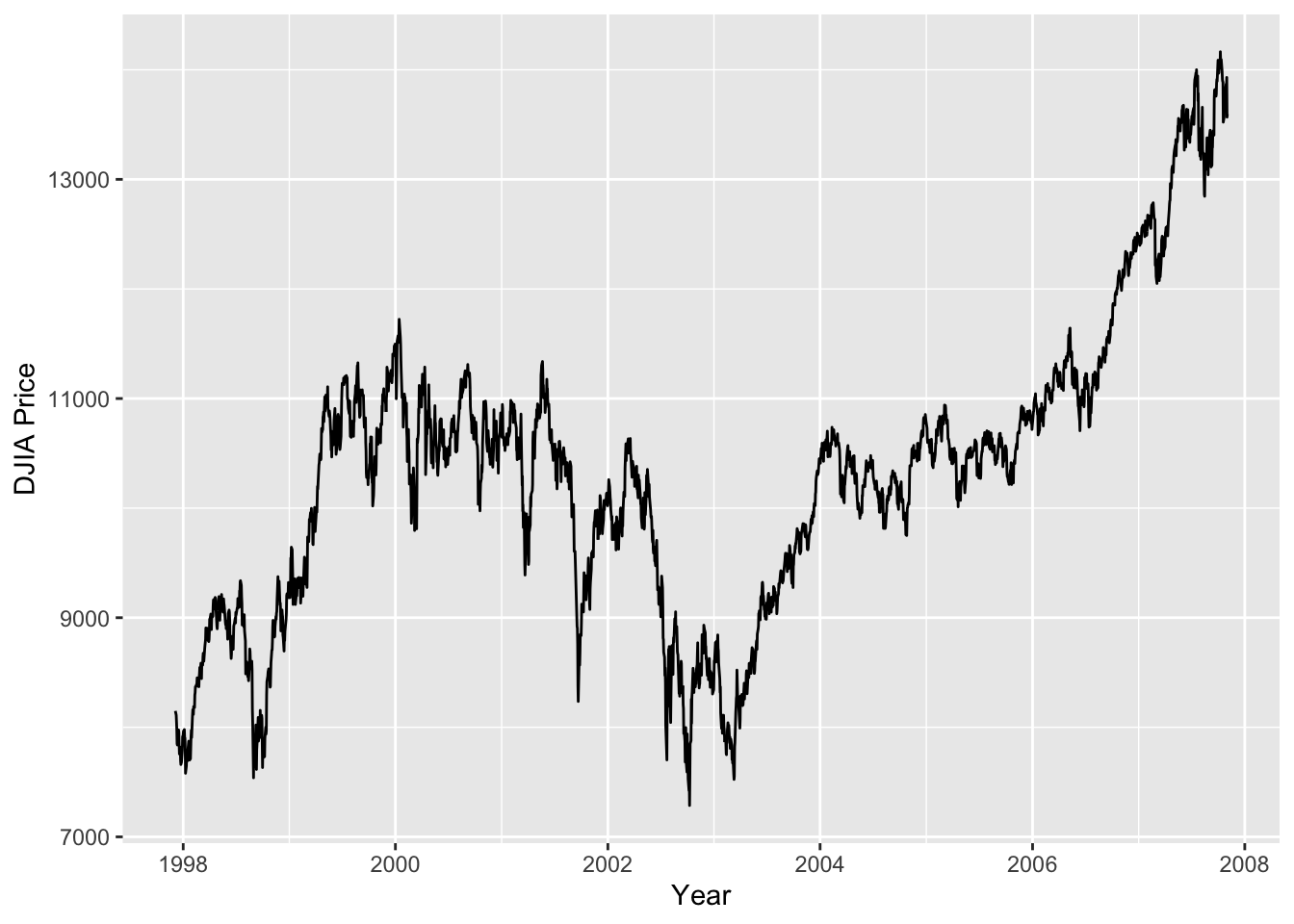

Figure 13.1 shows the closing price of the Dow Jones Industrial Average stock index for a period of about 10 years up until just before the 2008 recession, a period when stocks were considered a good investment. It’s evident that the price is going up and down in an irregular way, like a random walk. But it’s also true that the price at the end of the period is much higher than the price at the start of the period.

Figure 13.1: The closing price of the DJIA each day over 2500 trading days - a roughly 10 year period from the close on Dec. 5, 1997 to the close on Nov. 14, 2007. See Section 1.9 for an update on stock prices.

Is there a trend or is this just a random walk? It’s undeniable that there are fluctuations that look something like a random walk, but is there a trend buried under the fluctuations?

As phrased, the question contrasts two different possible hypotheses. The first is that the market is a pure random walk. The second is that the market has a systematic trend in addition to the random walk.

The natural question to ask is this: Which hypothesis is right?

Each of the hypotheses is actually a model: a representation of the world for a particular purpose. But each of the models is an incomplete representation of the world, so each is wrong.

It’s tempting to rephrase the question slightly to avoid the simplistic idea of right versus wrong models: Which hypothesis is a better approximation to the real world? That’s a nice question, but how to answer it in practice? To say how each hypothesis differs from the real world, you need to know already what the real world is like: Is there a trend in stock prices or not? That approach won’t take you anywhere.

Another idea: Which hypothesis gives a better match to the data? This seems a simple matter: fit each of the models to the data and see which one gives the better fit. But recall that even junk model terms can lead to smaller residuals. In the case of the stock market data, it happens that the model that includes a trend will almost always give smaller residuals than the pure random walk model, even if the data really do come from a pure random walk.

The logic of hypothesis testing avoids these problems. The basic idea is to avoid having to reason about the real world by setting up a hypothetical world that is completely understood. The observed patterns of the data are then compared to what would be generated in the hypothetical world. If they don’t match, then there is reason to doubt that the data support the hypothesis.

13.2 An Example of a Hypothesis Test

To illustrate the basic structure of a hypothesis test, here is one using the stock-market data.

The test statistic is a number that is calculated from the data and summarizes the observed patterns of the data. A test statistic might be a model coefficient or an R² value or something else. For the stock market data, it’s sensible to use as the test statistic the start-to-end dollar difference in prices over the 2500-day period. The observed value of this test statistic is $5446 - the DJIA stocks went up by this amount over the 10-year period.

The start-to-end difference can be used to test the hypothesis that the stock market is a random walk. (The reason to choose the random walk hypothesis for testing instead of the trend hypothesis will be discussed later.)

In order to carry out the hypothesis test, you construct a conjectural or hypothetical world in which the hypothesis is true. You can do this by building a simulation of that world and generating data from the simulation. Traditionally, such simulations have been implemented using probability theory and algebra to carry out the calculations of what results are likely in the hypothetical world. It’s also possible to use direct computer simulation of the hypothetical world.

The challenge is to create a hypothetical world that is relevant to the real world. It would not, for example, be relevant to hypothesize that stock prices never change, nor would it be relevant to imaging that they change by an unrealistic amount. Later chapters will introduce a few techniques for doing this in statistical models. For this stock-price hypothesis, we’ll imagine a hypothetical world in which prices change randomly up and down by the same daily amounts that they were seen to change in the real world.

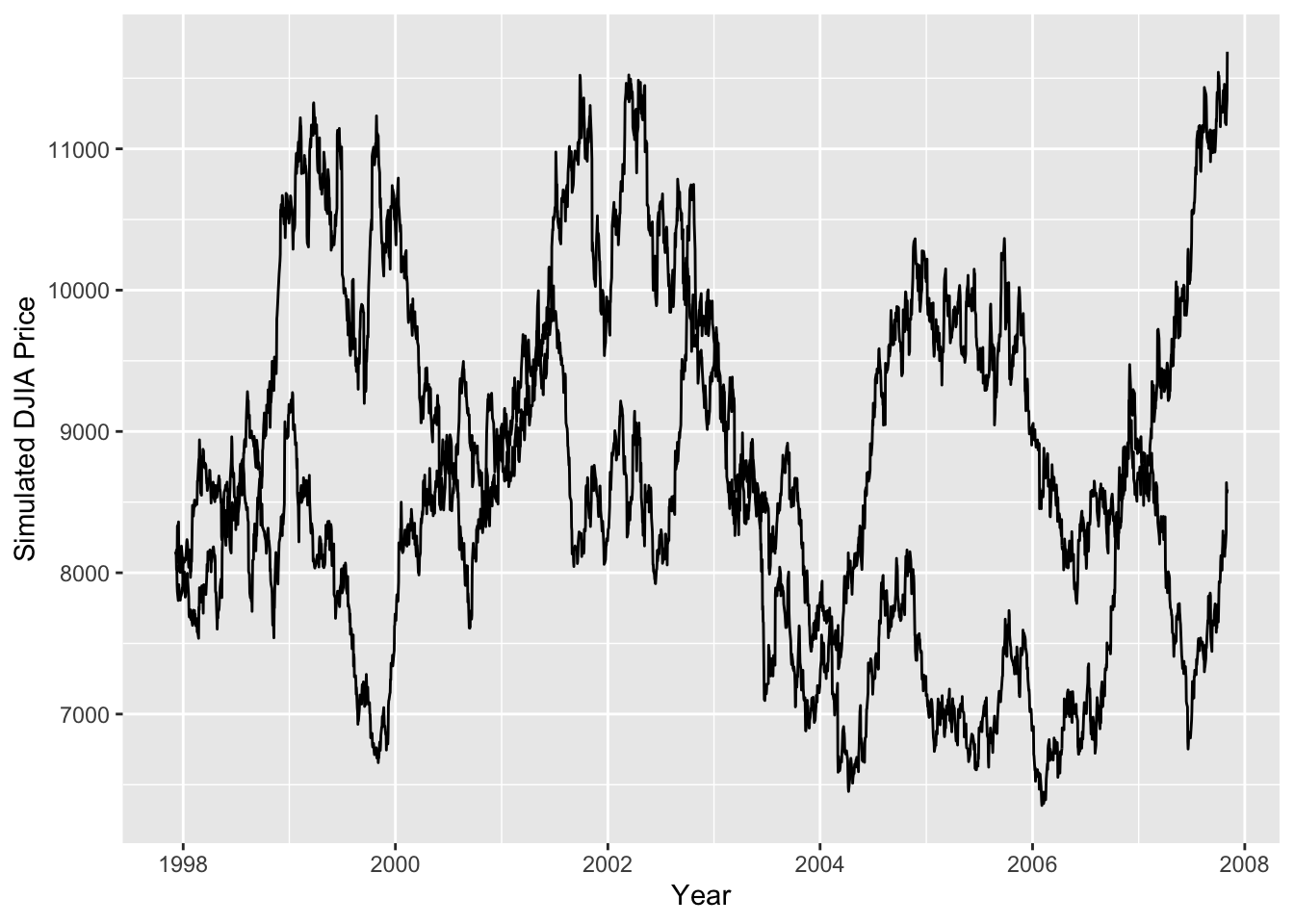

Figure 13.2 shows a few examples of stock prices in the hypothetical world where prices are equally likely to go up or down each day by the same daily percentages seen in the actual data.

Figure 13.2: Two simulations of stock prices in a hypothetical world where the day-to-day change is equally likely to be up or down.

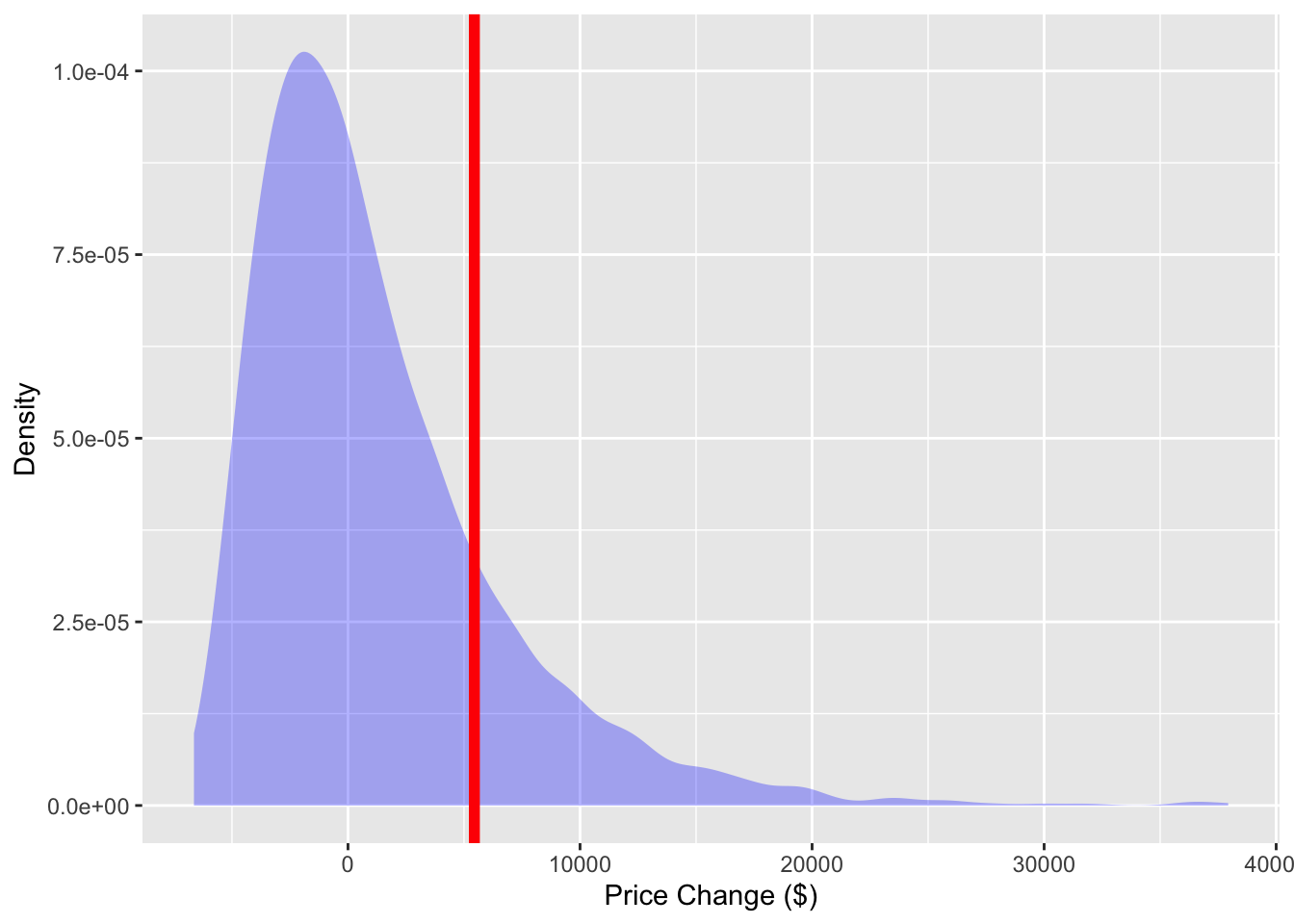

By generating many such simulations, and measuring from each individual simulation the start-to-end change in price, you get an indication of the range of likely outcomes in the hypothetical world. This is shown in Figure 13.3, which also shows the value observed in the real world - a price increase of $5446.

Figure 13.3: The distribution of start-to-end differences in stock price in the hypothetical world where that day-to-day changes in price are equally likely to be up or down by the proportions observed in the real world. The value observed in the data, $5446, is marked with a vertical line.

Since the observed start-to-end change in price is well within the possibilities generated by the simulation, it’s tempting to say, “the observations support the hypothesis.” For reasons discussed in the next section, however, the logically permitted conclusion is stiff and unnatural: We fail to reject the hypothesis.

13.3 Inductive and Deductive Reasoning

Hypothesis testing involves a combination of two different styles of reasoning: deduction and induction. In the deductive part, the hypothesis tester makes an assumption about how the world works and draws out, deductively, the consequences of this assumption: what the observed value of the test statistic should be if the hypothesis is true. For instance, the hypothesis that stock prices are a random walk was translated into a statement of the probability distribution of the start-to-end price difference.

In the inductive part of a hypothesis test, the tester compares the actual observations to the deduced consequences of the assumptions and decides whether the observations are consistent with them.

Deductive Reasoning

Deductive reasoning involves a series of rules that bring you from given assumptions to the consequences of those assumptions. For example, here is a form of deductive reasoning called a syllogism:

- Assumption 1: No healthy food is fattening.

- Assumption 2: All cakes are fattening.

- Conclusion: No cakes are healthy.

The actual assumptions involved here are questionable, but the pattern of logic is correct. If the assumptions were right, the conclusion would be right also.

Deductive reasoning is the dominant form in mathematics. It is at the core of mathematical proofs and lies behind the sorts of manipulations used in algebra. For example, the equation 3x + 2 = 8 is a kind of assumption. Another assumption, known to be true for numbers, is that subtracting the same amount from both sides of an equation preserves the equality. So you can subtract 2 from both sides to get 3x = 6. The deductive process continues - divide both sides by 3 - to get a new statement, x = 2, that is a logical consequence of the initial assumption. Of course, if the assumption 3x + 2 = 8 was wrong, then the conclusion x = 2 would be wrong too.

The contrapositive is a way of recasting an assumption in a new form that will be true so long as the original assumption is true. For example, suppose the original assumption is, “My car is red.” Another way to state this assumption is as a statement of implication, an if-then statement:

- Assumption: If it is my car, then it is red.

To form the contrapositive, you re-arrange the assumption to produce another statement:

- Contrapositive If it is not red, then it is not my car.

Any assumption of the form “if [statement 1] then [statement 2]” has a contrapositive. In the example, statement 1 is “it is my car.” Statement 2 is “it is red.” The contrapositive looks like this:

- Contrapositive: If [negate statement 2] then [negate statement 1].

The contrapositive is, like algebraic manipulation, a re-rearrangement: reverse and negate. Reversing means switching the order of the two statements in the if-then structure. Negating a statement means saying the opposite. The negation of “it is red” is “it is not red.” The negation of “it is my car” is “it is not my car.” (It would be wrong to say that the negation of “it is my car” is “it is your car.” Clearly it’s true that if it is your car, then it is not my car. But there are many ways that the car can be not mine and yet not be yours. There are, after all, many other people in the world than you and me!)

Contrapositives often make intuitive sense to people. That is, people can see that a contrapostive statement is correct even if they don’t know the name of the logical re-arrangement. For instance, here is a variety of ways of re-arranging the two clauses in the assumption, “If that is my car, then it is red.” Some of the arrangements are logically correct, and some aren’t.

Original Assumption: If it is my car, then it is red.

Negate first statement: If it is not my car, then it is red.

Wrong. Other people can have cars that are not red.Negate only second statement: If it is my car, then it is not red.

Wrong. The statement contradicts the original assumption that my car is red.Negate both statements: If it is not my car, then it is not red.

Wrong. Other people can have red cars.Reverse statements: If it is red, then it is my car.

Wrong. Apples are red and they are not my car. Even if it is a car, not every red car is mine.Reverse and negate first: If it is red, then it is not my car.

Wrong. My car is red.Reverse and negate second: If it is not red, then it is my car.

Wrong. Oranges are not red, and they are not my car.Reverse and negate both - the contrapositive: If it is not red, then it is not my car.

Correct.

Inductive Reasoning

In contrast to deductive reasoning, inductive reasoning involves generalizing or extrapolating from a set of observations to conclusions. An observation is not an assumption: it is something we see or otherwise perceive. For instance, you can go to Australia and see that kangaroos hop on two legs. Every kangaroo you see is hopping on two legs. You conclude, inductively, that all kangaroos hop on two legs.

Inductive conclusions are not necessarily correct. There might be one-legged kangaroos. That you haven’t seen them doesn’t mean they can’t exist. Indeed, Europeans believed that all swans are white until explorers discovered that there are black swans in Australia.

Suppose you conduct an experiment involving 100 people with fever. You give each of them aspirin and observe that in all 100 the fever is reduced. Are you entitled to conclude that giving aspirin to a person with fever will reduce the fever? Not really. How do you know that there are no people who do not respond to aspirin and who just happened not be be included in your study group?

Perhaps you’re tempted to hedge by weakening your conclusion: “Giving aspirin to a person with fever will reduce the fever most of the time.” This seems reasonable, but it is still not necessarily true. Perhaps the people in you study had a special form of fever-producing illness and that most people with fever have a different form.

By the standards of deductive reasoning, inductive reasoning does not work. No reasonable person can argue about the deductive, contrapositive reasoning concerning the red car. But reasonable people can very well find fault with the conclusions drawn from the study of aspirin.

Here’s the difficulty. If you stick to valid deductive reasoning, you will draw conclusions that are correct given that your assumptions are correct. But how can you know if your assumptions are correct? How can you make sure that your assumptions adequately reflect the real world? At a practical level, most knowledge of the world comes from observations and induction.

The philosopher David Hume noted the everyday inductive “fact” that food nourishes us, a conclusion drawn from everyday observations that people who eat are nourished and people who do not eat waste away. Being inductive, the conclusion is suspect. Still, it would be a foolish person who refuses to eat for want of a deductive proof of the benefits of food.

Inductive reasoning may not provide a proof, but it is nevertheless useful.

13.4 The Null Hypothesis

A key aspect of hypothesis testing is the choice of the hypothesis to test. The stock market example involved testing the random-walk hypothesis rather than the trend hypothesis. Why? After all, the hypothesis of a trend is more interesting than the random-walk hypothesis; it’s more likely to be useful if true.

It might seem obvious that the hypothesis you should test is the hypothesis that you are most interested in. But this is wrong.

In a hypothesis test one assumes that the hypothesis to be tested is true and draws out the consequences of that assumption in a deductive process. This can be written as an if-then statement:

If hypothesis H is true, then the test statistic S will be drawn from a probability distribution P.

For example, in the stock market test, the assumption that the day-to-day price change is random leads to the conclusion that the test statistic - the start-to-end price difference - will be a draw from the distribution shown in Figure 13.3.

The inductive part of the test involves comparing the observed value of the test statistic S to the distribution P. There are two possible outcomes of this comparison:

- Agreement: S is a plausible outcome from P.

- Disagreement: S is not a plausible outcome from P.

Suppose the outcome is agreement between S and P. What can be concluded? Not much. Recall the statement “If it is my car, then it is red.” An observation of a red car does not legitimately lead to the conclusion that the car is mine. For an if-then statement to be applicable to observations, one needs to observe the if-part of the statement, not the then-part.

An outcome of disagreement gives a more interesting result, because the contrapositive gives logical traction to the observation; “If it is not red, then it is not my car.” Seeing “not red” implies “not my car.” Similarly, seeing that S is not a plausible outcome from P, tells you that H is not a plausible possibility. In such a situation, you can legitimately say, “I reject the hypothesis.”

Ironically, in the case of observing agreement between S and P, the only permissible statement is, “I fail to reject the hypothesis.” You certainly aren’t entitled to say that the evidence causes you to accept the hypothesis.

This is an emotionally unsatisfying situation. If your observations are consistent with your hypothesis, you certainly want to accept the hypothesis. But that is not an acceptable conclusion when performing a formal hypothesis test. There are only two permissible conclusions from a formal hypothesis test:

- I reject the hypothesis.

- I fail to reject the hypothesis.

In choosing a hypothesis to test, you need to keep in mind two criteria.

- Criterion 1: The only possible interesting outcome of a hypothesis test is “I reject the hypothesis.” So make sure to pick a hypothesis that it will be interesting to reject.

The role of the hypothesis is to be refuted or nullified, so it is called the null hypothesis.

What sorts of statements are interesting to reject? Often these take the form of the conventional wisdom or a claim of no effect.

For example, in comparing two fever-reducing drugs, an appropriate null hypothesis is that the two drugs have the same effect. If you reject the null, you can say that they don’t have the same effect. But if you fail to reject the null, you’re in much the same position as before you started the study.

Failing to reject the null may mean that the null is true, but it equally well may mean only that your work was not adequate: not enough data, not a clever enough experiment, etc. Rejecting the null can reasonably be taken to indicate that the null hypothesis is false, but failing to reject the null tells you very little.

- Criterion 2: To perform the deductive stage of the test, you need to be able to calculate the range of likely outcomes of the test statistic. This means that the hypothesis needs to be specific.

The assumption that stock prices are a random walk has very definite consequences for how big a start-to-end change you can expect to see. On the other hand, the assumption “there is a trend” leaves open the question of how big the trend is. It’s not specific enough to be able to figure out the consequences.

13.5 The p-value

One of the consequences of randomness is that there isn’t a completely clean way to say whether the observations fail to match the consequences of the null hypothesis. In principle, this is a problem even with simple statements like “the car is red.” There is a continuous range of colors and at some point one needs to make a decision about how orange the car can be before it stops being red.

Figure 13.3 shows the probability distribution for the start-to-end stock price change under the null hypothesis that stock prices are a random walk. The observed value of the test statistic, $5446, falls under the tall part of the curve - it’s a plausible outcome of a random draw from the probability distribution.

The conventional way to measure the plausibility of an outcome is by a p-value . The p-value of an observation is always calculated with reference to a probability distribution derived from the null hypothesis.

P-values are closely related to percentiles. The observed value $5446 falls at the 81rd percentile of the distribution. An observation that’s at or beyond the extremes of the distribution is implausible. This would correspond to either very high percentiles or very low percentiles. Being at the 81rd percentile implies that 19 percent of draws would be even more extreme, falling even further to the right than $5446.

The p-value is the fraction of possible draws from the distribution that are as extreme or more extreme than the observed value. If the concern is only with values bigger than $5446, then the p-value is 0.19.

A small p-value indicates that the actual value of the test statistic is quite surprising as an outcome from the null hypothesis. A large p-value means that the test statistic value is run of the mill, not surprising, not enough to satisfy the “if” part of the contrapositive.

The convention in hypothesis testing is to consider the observation as being implausible when the p-value is less than 0.05. In the stock market example, the p-value is larger than 0.05, so the outcome is to fail to reject the null hypothesis that stock prices are a random walk with no trend.

13.6 Rejecting by Mistake

The p-value for the hypothesis test of the possible trend in stock-price was 0.19, not small enough to justify rejecting the null hypothesis that stock prices are a random walk with no trend. A smaller p-value, one less than 0.05 by convention, would have led to rejection of the null. The small p-value would have indicated that the observed value of the test statistic was implausible in a world where the null hypothesis is true.

Now turn this around. Suppose the null hypothesis really were true; suppose stock prices really are a random walk with no trend. In such a world, it’s still possible to see an implausible value of the test statistic. But, if the null hypothesis is true, then seeing an implausible value is misleading; rejecting the null is a mistake. This sort of mistake is called a Type I error.

Such mistakes are not uncommon. In a world where the null is true - the only sort of world where you can falsely reject the null - they will happen 5% of the time so long as the threshold for rejecting the null is a p-value of 0.05.

The way to avoid such mistakes is to lower the p-value threshold for rejecting the null. Lowering it to, say, 0.01, would make it harder to mistakenly reject the null. On the other hand, it would also make it harder to correctly reject the null in a world where the null ought to be rejected.

The threshold value of the p-value below which the null should be rejected is a probability: the probability of rejecting the null in a world where the null hypothesis is true. This probability is called the significance level of the test.

It’s important to remember that the significance level is a conditional probability. It is the probability of rejecting the null in a world where the null hypothesis is actually true. Of course that’s a hypothetical world, not necessarily the real world.

13.7 Failing to Reject

In the stock-price example, the large p-value of 0.19 led to a failure to reject the null hypothesis that stock prices are a random walk. Such a failure doesn’t mean that the null hypothesis is true, although it’s encouraging news to people who want to believe that the null hypothesis is true.

You never get to “accept the null” because there are reasons why, even if the null were wrong, it might not have been rejected:

- You might have been unlucky. The randomness of the sample might have obscured your being able to see the trend in stock prices.

- You might not have had enough data. Perhaps the trend is small and can’t easily be seen.

- Your test statistic might not be sensitive to the ways in which the system differs from the null hypothesis. For instance, suppose that there is an small average tendency for each day’s activity on the stock market to undo the previous day’s change: the walk isn’t exactly random. Looking for large values of the start-to-end price difference will not reveal this violation of the null. A more sensitive test statistic would be the correlation between price changes on successive days.

A helpful idea in hypothesis testing is the alternative hypothesis: the pet idea of what the world is like if the null hypothesis is wrong. The alternative hypothesis plays the role of the thing that you would like to prove. In the hypothesis-testing drama, this is a very small role, since the only possible outcomes of a hypothesis test are (1) reject the null and (2) fail to reject the null. The alternative hypothesis is not directly addressed by the outcome of a hypothesis test.

The role of the alternative hypothesis is to guide you in interpreting the results if you do fail to reject the null. The alternative hypothesis is also helpful in deciding how much data to collect.

To illustrate, suppose that the stock market really does have a trend hidden inside the random day-to-day fluctuations with a standard deviation of $106.70. Imagine that the trend is $2 per day: a pet hypothesis.

Suppose the world really were like the alternative hypothesis. What is the probability that, in such a world, you would end up failing to reject the null hypothesis? Such a mistake, where you fail to reject the null in a world where the alternative is actually true, is called a Type II error.

This logic can be confusing at first. It’s tempting to reason that, if the alternative hypothesis is true, then the null must be false. So how could you fail to reject the null? And, if the alternative hypothesis is assumed to be true, why would you even consider the null hypothesis in the first place?

Keep in mind that neither the null hypothesis nor the alternative hypothesis should be taken as “true.” They are just competing hypotheses, conjectures used to answer “what-if?” questions.

Aside: Calculating a Power

Here are the steps in calculating the power of the hypothesis test of stock market prices. The null hypothesis is that prices are a pure random walk as illustrated in Figure 13.2. The alternative hypothesis is that in addition to the random component, the stock prices have a systematic trend of increasing by $2 per day.

- Go back to the null hypothesis world and find the thresholds for the test statistic that would cause you to reject the null hypothesis. Referring to Figure , you can see that a test statistic of $11,000 would have produced a p-value of 0.05.

- Now return to the alternative hypothesis world. In this world, what is the probability that the test statistic would have been bigger than $11,000? This question can be answered by the same sort of simulation as in Figure but with a $2 price increase added each day. Doing the calculation gives a probability of \(0.16\).

Section 13.7 discusses power calculations for models.

The probability of rejecting the null in a world where the alternative is true is called the power of the hypothesis test. Of course, if the alternative is true, then it’s completely appropriate to reject the null, so a large power is desirable.

A power calculation involves considering both the null and alternative hypotheses. The aside in Section 13.7 shows the logic applied to the stock-market question. It results in a power of 16%.

The power of 16% for the stock market test means that even if the pet theory of the $2 daily trend were correct, there is only a 16% chance of rejecting the null. In other words, the study is quite weak.

When the power is small, failure to reject the null can reasonably be interpreted as a failure in the modeler (or in the data collection or in the experiment). The study has given very little information.

Just because the power is small is no reason to doubt the null hypothesis. Instead, you should think about how to conduct a better, more powerful study.

One way a study can be made more powerful is to increase the sample size. Fortunately, it’s feasible to figure out how large the study should be to achieve a given power. The reason is that the power depends on the two hypotheses: the null and the alternative. In carrying out the simulations using the null and alternative hypotheses, it’s possible to generate any desired amount of simulated data. It turns out that reliably detecting - a power of 80% - a $2 per day trend in stock prices requires about 75 years worth of data. This long historical period is probably not relevant to today’s investor. Indeed, it’s just about all the data that is actually available: the DJIA was started in 1928.

When the power is small for realistic amounts of data, the phenomenon you are seeking to find may be undetectable.

13.8 A Glossary of Hypothesis Testing

- Null Hypothesis: A statement about the world that you are interested to disprove. The null is almost always something that is clearly relevant and not controversial: that the conventional wisdom is true or that there is no relationship between variables. Examples: “The drug has no influence on blood pressure.” “Smaller classes do not improve school performance.”

The allowed outcomes of the hypothesis test relate only to the null:

- Reject the null hypothesis.

- Fail to reject the null hypothesis.

Alternative Hypothesis: A statement about the world that motivates your study and stands in contrast to the null hypothesis. “The drug will reduce blood pressure by 5 mmHg on average.” So, one possible alternative hypothesis is that “Decreasing class size from 30 to 25 will improve test scores by 3%.”

The outcome of the hypothesis test is not informative about the alternative. The importance of the alternative is in setting up the study: choosing a relevant test statistic and collecting enough data.

Test Statistic: The number that you use to summarize your study. This might be the sample mean, a model coefficient, or some other number. Later chapters will give several examples of test statistics that are particularly appropriate for modeling.

Type I Error: A wrong outcome of the hypothesis test of a particular type. Suppose the null hypothesis were really true. If you rejected it, this would be an error: a type I error.

Type II Error: A wrong outcome of a different sort. Suppose the alternative hypothesis were really true. In this situation, failing to reject the null would be an error: a type II error.

Significance Level:

A conditional probability. In the world where the null hypothesis is true, the significance is the probability of making a type I error. Typically, hypothesis tests are set up so that the significance level will be less than 1 in 20, that is, less than 0.05. One of the things that makes hypothesis testing confusing is that you do not know whether the null hypothesis is correct; it is merely assumed to be correct for the purposes of the deductive phase of the test. So you can’t say what is the probability of a type I error. Instead, the significance level is the probability of a type I error assuming that the null hypothesis is correct.

Ideally, the significance level would be zero. In practice, one accepts the risk of making a type I error in order to reduce the risk of making a type II error.

- p-value: This is the usual way of presenting the result of the hypothesis test. It is a number that summarizes how atypical the observed value of the test statistic would be in a world where the null hypothesis is true. The convention for rejecting the null hypothesis is p < 0.05.

The p-value is closely related to the significance level. It is sometimes called the achieved significance level .

- Power: This is a conditional probability. But unlike the significance, the condition is that the alternative hypothesis is true. The power is the probability that, in the world where the alternative is true, you will reject the null. Ideally, the power should be 100%, so that if the alternative really were true the null hypothesis would certainly be rejected. In practice, the power is less than this and sometimes much less.

In science, there is an accepted threshold for the p-value: \(0.05\). But, somewhat strangely, there is no standard threshold for the power. When you see a study which failed to reject the null, it is helpful to know what the power of the study was. If the power was small, then failing to reject the null is not informative.

13.9 Update on Stock Prices

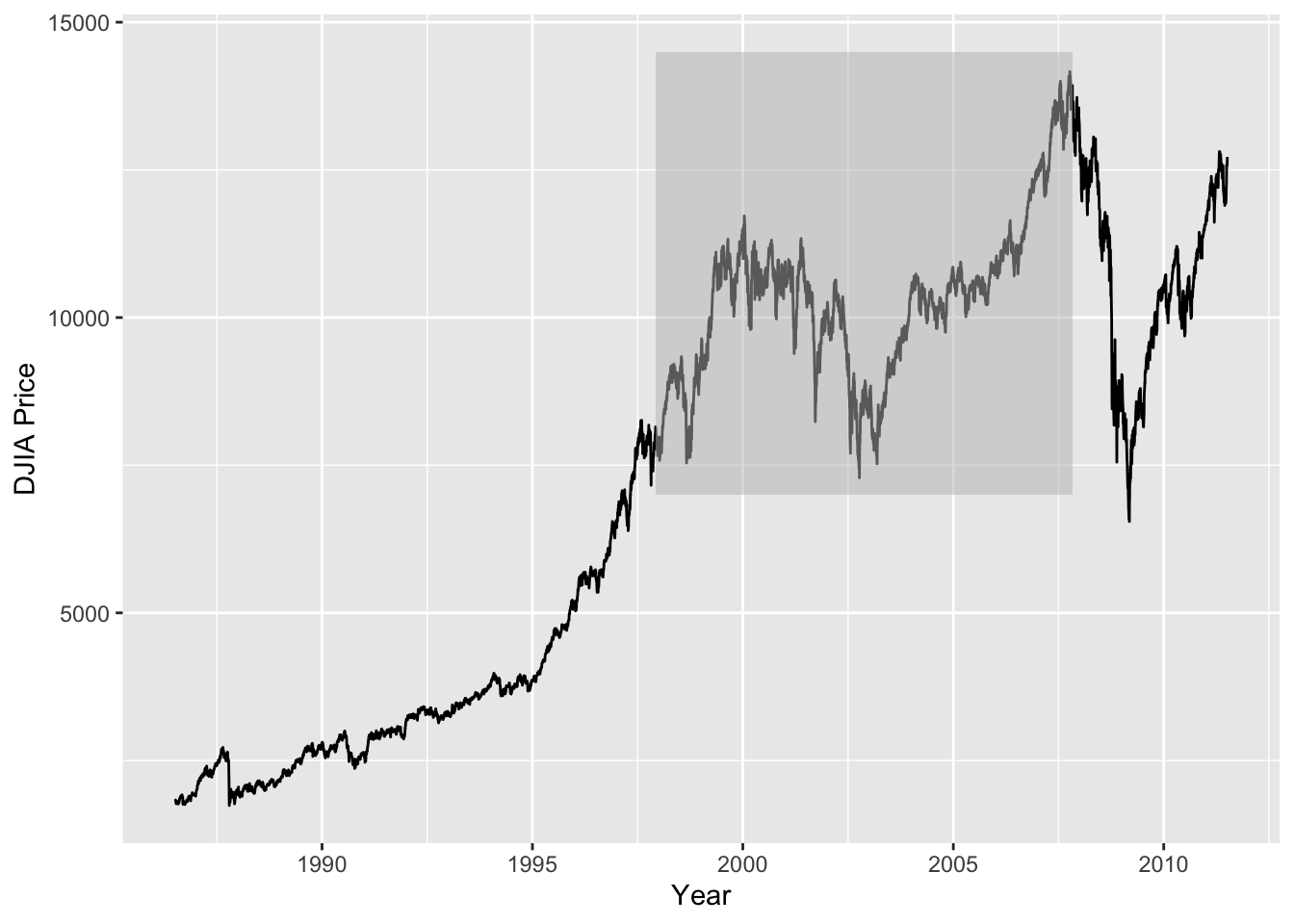

Figure 13.1 shows stock prices over the 10-year period from Dec. 5, 1997 to Nov. 14, 2007. For comparison, Figure 13.4 shows a wider time period, the 25-year period from 1985 to the month this section is being written in 2011.

When the first edition of this book was being written, in 2007, the 10-year period was a natural sounding interval, but a bit more information on the choice can help to illuminate a potential problem with hypothesis testing. I wanted to include a stock-price example because there is such a strong disconnection between the theories of stock prices espoused by professional economists - daily changes are a random walk - and the stories presented in the news, which wrongly provide a specific daily cause for each small change and see “bulls” and “bears” behind month- and year-long trends. I originally planned a time frame of 5 years - a nice round number. But the graph of stock prices from late 2002 to late 2007 shows a pretty steady upward trend, something that’s visually inconsistent with the random-walk null hypothesis. I therefore changed my plan, and included 10-years worth of data. If I had waited another year, through the 2008 stock market crash, the upward trend would have been eliminated. In 2010 and early 2011, the market climbed up again, only to fall dramatically in mid-summer.

That change from 5 to 10 years was inconsistent with the logic of hypothesis testing. I was, in effect, changing my data - by selecting the start and end points - to make them more consistent with the claim I wanted to make. This is always a strong temptation, and one that ought to be resisted or, at least, honestly accounted for.

Figure 13.4: Closing prices of the Dow Jones Industrial Average for the 25 years before July 9, 2011, the date on which the plot was made. The sub-interval used in this book’s first edition is shaded.