The {LST} package provides support for the style of R

computing used in the textbook, Lessons

in Statistical Thinking. This style seeks to reduce the

cognitive load on students by reducing to a minimum the number of R

functions and the syntax needed to undertake a complete course that

includes (simple) data wrangling, visualization, modeling, and causal

simulation. At the same time, the style supports using statistical

inference in an informal way from the very beginning of the course,

gradually formalizing it over the semester.

This document is oriented toward instructors or strongly motivated

students. The Lessons textbook and accompanying blog posts provide an

introduction for the typical student. The reader of this document should

already know at least a little about R: basics of data frames as well as

functions and function calls, named arguments, and R “formulas” (such as

mpg ~ hp + cyl) which are called tilde

expressions in Lessons. (Statistics students need to

use mathematical formulas from time to time, so best not confuse math

formulas with an unneeded name for an R syntactical structure.)

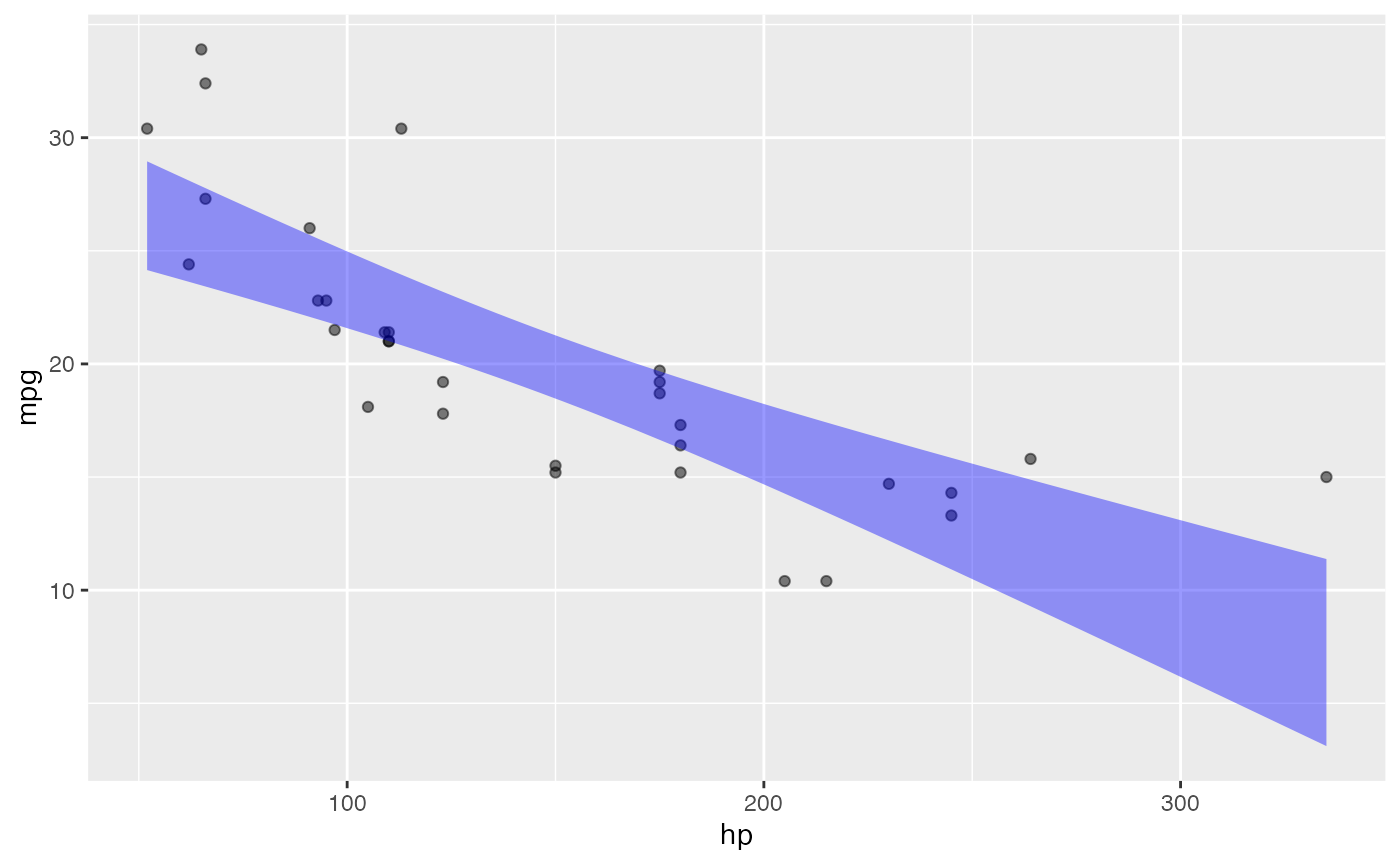

A command template

R commands in Lessons are well exemplified by the following: generating a plot of two variables in a data frame and then annotating the plot with a simple linear model.

mtcars |> point_plot(mpg ~ hp, annot = "model")

The command illustrates several features of the style of commands in Lessons:

-

The basic structure involves piping a data frame into a function. The pipeline structure is used almost exclusively in Lessons. For the reader not acquainted with the R pipe, the object on the left-hand side of the pipe token

|>becomes the first argument to the function call on the right-hand side.- The left-hand side of the pipe—the input end of the pipe–will very often be a data frame, but a handful of other types are used in that role in Lessons. (More on this later.)

- The right-hand side—the output end of the pipe–will always be a function call.

-

Variables in the data frame are referred to by unquoted name. Such variable names are only used in the role of an un-piped argument to the right-hand side function call.

- The

$notation is never used in any setting. - For situations in which there is a response variable (as in modeling or graphics), the variable names always appear in tilde expressions.

- The

Often, a tilde expression will be the only thing inside the parentheses that follow the function name. But sometimes additional details for the function will be added within the parentheses. In the above example command, the detail to add a statistical model as an annotation is specified by the argument `annot = “model”.

-

point_plot()is a omnibus graphics command sufficient for teaching an entire statistics course that includes inference and covariation.- The output is ggplot2 compatible.

- Other such omnibus commands from

{LST}seen in Lessons aremodel_train(),sample(), andtrials(). - Wrangling functions from dplyr are also occasionally

used, especially

mutate()andsummarize(). - Summaries of statistical models are made with the

{LST}functionconf_interval()and occasionallyR2(). (Near the end of the course,regression_summary()andanova_summary()are introduced, but these play only a very minor, optional role in the course.)

Pipe input-ends

I’m using the term input end of a pipe to refer to

the object on the left-hand side of the |> pipe token.

There are only a handful of types presented to the input end of the

pipe:

- A data frame is by far the most common input type.

- A statistical model is an input type used frequently in the second-half of the course.

- A “data simulation” is another kind of input type.

- Optionally, and mainly for enrichment, a data graphic frame (as

produced by

point_plot()) is used at the input of the pipe towards a command to add labels or to add another ggplot2 layer.

Pipe output-ends

Just as input end refers to the object provided at the left-hand side of the pipe, the object produced by the function call on the right side is the pipe’s output. Two essential points about pipe output-ends:

The R command given on the right-hand side of

|>will always be a function call. No exceptions. A function call consists of the name of a function (e.g.,point_plotormodel_train) followed by an open/closed pair of parentheses. Usually, there is something such as a tilde expression contained in the parentheses, but there are often additional named arguments such as theannot = "model"in the example command presented in @sec-command-template.The function call in (a) produces an R object. For the

{LST}functions, this object will always be one of the four types presented in the previous section (data frame, model, data simulation, graphics frame).

Multi-stage pipelines

The object produced by the function call at the output end of the

pipe |> can provide the input, via another

pipe, to another function call. This technique is often used for data

wrangling or when summarizing a model. For instance, the following

converts fuel “economy” (mpg) into fuel

consumption (liters per 100 km), which is then used as the

response variable in a model.

mtcars |>

dplyr::mutate(consumption = 235.2 / mpg) |>

model_train(consumption ~ hp + wt) |>

conf_interval()

#> # A tibble: 3 × 4

#> term .lwr .coef .upr

#> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 (Intercept) -0.486 1.48 3.45

#> 2 hp 0.00647 0.0176 0.0287

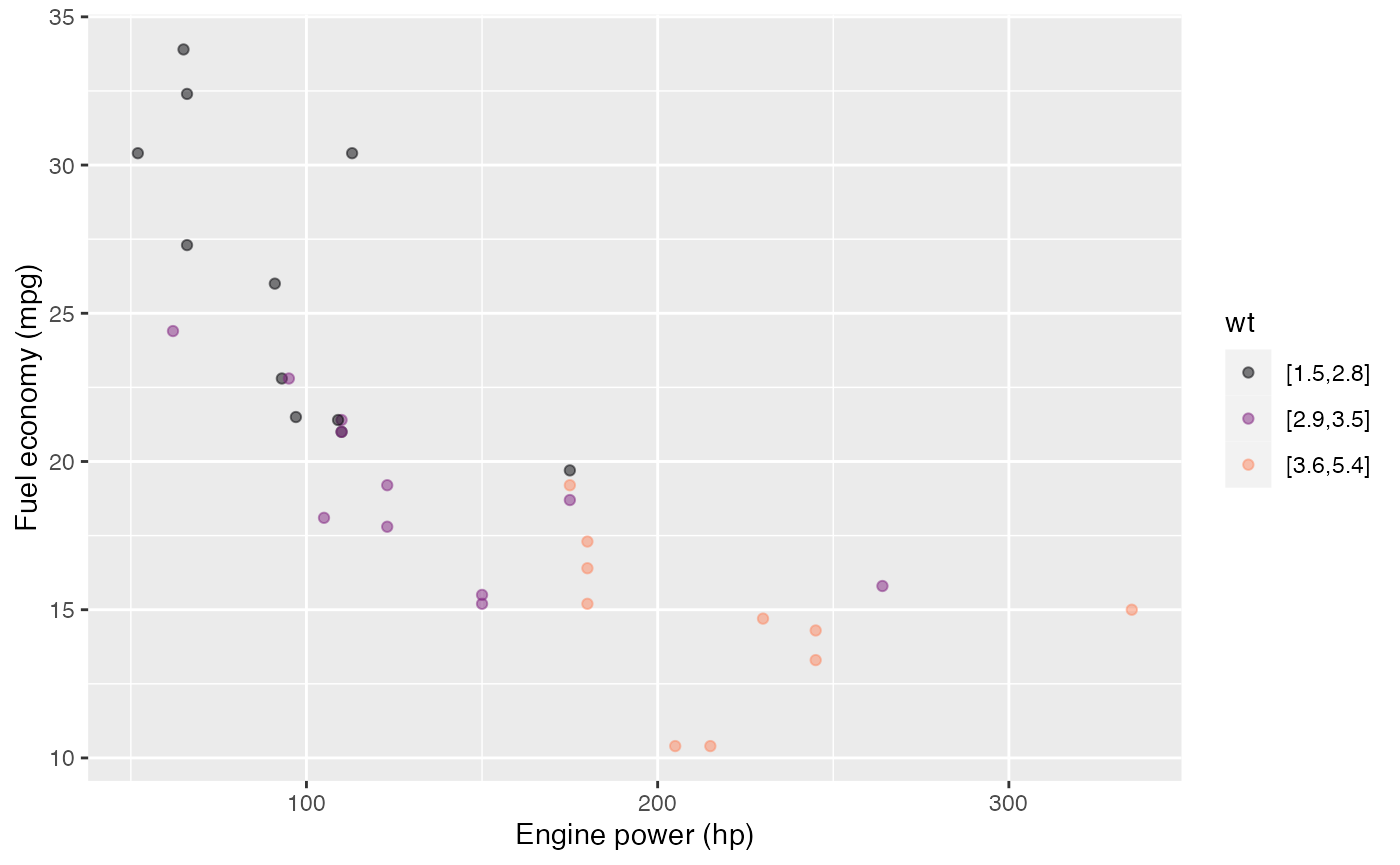

#> 3 wt 1.92 2.70 3.48For convenience, the add_plot_labels() function will

modify the labels in a plot, taking as input a plot (as produced by

point_plot(), for instance) and returning as output the

modified plot. (Perhaps of interest to those familiar with

ggplot2 … add_plot_labels() is merely a

wrapper on ggplot2::labs() that avoids the non-standard

+ pipe system.)

mtcars |>

point_plot(mpg ~ hp * wt) |>

add_plot_labels(x = "Engine power (hp)", y = "Fuel economy (mpg)")

What to do with the ultimate output of a pipeline?

The flow of computation in a pipeline runs from left to right. The output object from the last stage of the pipeline will, by default, be printed. The alternative is to store that output object under a name, using the “storage arrow”, like this:

storage_name <- pipeline

In R, the form in which an object is printed is controlled by the programmer. Graphics are typically “printed” by displaying the graphic in an appropriate place. Data frames are typically printed as text.

In addition to data frames and graphics, Lessons deals frequently with two other sorts of objects: data simulations and models.

By default, models are printed as text. There is a wide variety of

formats corresponding to the large number of people who have communally

put together the modeling systems in R. Rather than the hodge-podge of

printed model formats, I encourage users to print specific summaries of

models such as graphs of the model function (use

model_plot()). The numerical model summaries in

{LST} are always printed in data-frame format. Most of the

time in Lessons, models are summarized with coefficients and

confidence intervals, a format produced by conf_interval().

I strongly recommend that model coefficients always be shown in

the context of a confidence interval; conf_interval()

imposes this policy. Another sometimes useful format of summary is

provided by R2(). Toward the end of the course, the ANOVA

generalization of R2 is introduced.

anova_summary() is useful for comparing two or more models.

regression_summary() shows a standard regression report,

but conf_interval() is, I think, a superior format. (If you

feel obliged to show a p-value, use the show_p = TRUE

argument to conf_interval(). But I recommend focussing on

whether the confidence interval includes zero, using the

level = argument if you aren’t happy with 0.05.)

Data simulations are printed as text showing the causal formulas relating one variable to the others. Like this:

sim_06

#> $names

#> $names[[1]]

#> a

#>

#> $names[[2]]

#> b

#>

#> $names[[3]]

#> c

#>

#> $names[[4]]

#> d

#>

#>

#> $calls

#> $calls[[1]]

#> rnorm(n)

#>

#> $calls[[2]]

#> a + rnorm(n)

#>

#> $calls[[3]]

#> b + rnorm(n)

#>

#> $calls[[4]]

#> c + a + rnorm(n)

#>

#>

#> attr(,"class")

#> [1] "list" "datasim"Instructions for constructing data simulations are given in the

Simulating data with Directed Acyclic Graphs vignette of this

package. Many pre-built simulations are provided with this

{LST} package. New ones can be constructed using

datasim_make(). Except in the most straightforward cases,

such construction is an instructor-level task.

Trials and the pipe

A popular feature of the mosaic package is the

do() function, which provides syntax and logic for

repeating a command multiple times, accumulating the results into a data

frame. For instance:

{LST} has updated this functionality to take advantage

of the R built-in pipe notation and the style of arranging model

summaries as data frames. The functionality is provided by the

trials() function. To use it, place trials()

at the end of a pipeline:

mtcars |>

sample(replace = TRUE) |> # resampling here!

model_train(mpg ~ hp) |>

conf_interval() |>

filter(term == "hp") |>

trials(5)

#> .trial term .lwr .coef .upr

#> 1 1 hp -0.05884886 -0.04350439 -0.02815991

#> 2 2 hp -0.07123911 -0.05567061 -0.04010210

#> 3 3 hp -0.10945900 -0.08387168 -0.05828437

#> 4 4 hp -0.11131359 -0.08981114 -0.06830869

#> 5 5 hp -0.08612844 -0.06705820 -0.04798795You can, of course, take the data frame produced by

trials() to use for later wrangling or graphics.

It’s natural to think of the pipeline leading up to the

trials() stage as creating a single output. But

trials() has a seemingly magical ability to grab the whole

pipeline and run it over and over again. (The “magic” is provided by the

“non-standard evaluation” facilities in R, an advanced programming

construct.)

An excellent way to develop the statement to be repeated: write the

pipeline excluding the final trials() stage. Each

time you run the truncated pipeline, you will receive one object. When

this object has the format you seek, add the final trials()

stage back in.

Graphics in {LST}

Instructors may feel obliged by convention to introduce the menagerie

of plotting modalities, such as bar charts, line charts, histograms,

etc. Lessons was written to use only a single primary graphic

modality: the point plot (a.k.a. “scatter plot”) as produced by

point_plot(). Three other modalities—confidence intervals,

confidence bands, and violin plots of density—are provided by the

annotation feature of point_plot(). These are

annot = "violin" and "annot = "model".

The output of point_plot() is a ggplot2

graphical object. Consequently, you can use the various

ggplot2 functions to set a graphics theme, label axes,

and so on. Unfortunately, ggplot2 functions use the

+ pipe rather than |>. This can be

confusing and frustrating for students.

I recommend use of the ggformula package which

re-packages the ggplot2 facilities in a way that can be

used with the R pipe |> and which employe

tilde-expressions for specifying response and explanatory variables.

{LST}, {mosaic}, and

{ggformula}

The MOSAIC suite of packages—including mosaic and

ggformula—are widely used in teaching statistics with R.

Many of the pedagogical principles behind {LST} are shared

with mosaic and ggformula. You are of

course welcome to use mosaic and ggformula

along with {LST}, particularly if you want to teach other

graphics modalities than those provided by

LST::point_plot().

Other than shared pedagogical principles, there is no connection of

{LST} with either mosaic and

ggformula. One reason for this is the pipe

|>, which prominently features in Lessons.

mosaic is not pipe-ready because many functions require a

data = argument.

Another reason concerns recent developments in deploying R computing

via web pages. The system that provides within-a-web-page R

computing is not yet compatible with mosaic or

ggformula. For {LST} to work with R embedded

in web pages, {LST} cannot make any use of

mosaic/ggformula. This situation may

change in the future, at which point {LST} will be able to

acknowledge its aunts and uncles.