Chapter 14 Some history

Jerome Cornfield considering Fisher’s proposal that a confounder, not smoking, is responsible for lung cancer and the observed correlation of smoking with cancer. Reading: Schield-1999

The question he addressed: How strong would the hypothetical confounder have to be to account entirely for the observed relationship between smoking and cancer?

In the following A = smoking, B = Fisher’s confounder. The risk ratio, r, was already known to be about 9.

If an agent, A, with no causal effect upon the risk of a disease, nevertheless, because of a positive correlation with some other causal agent, B, shows an apparent risk, r, for those exposed to A, relative to those not so exposed, then the prevalence of B, among those exposed to A, relative to the prevalence among those not so exposed, must be greater than r. – Cornfield J et al. Smoking and lung cancer: recent evidence and a discussion of some questions. JNCI 1959;22:173–203. Reprint available here.

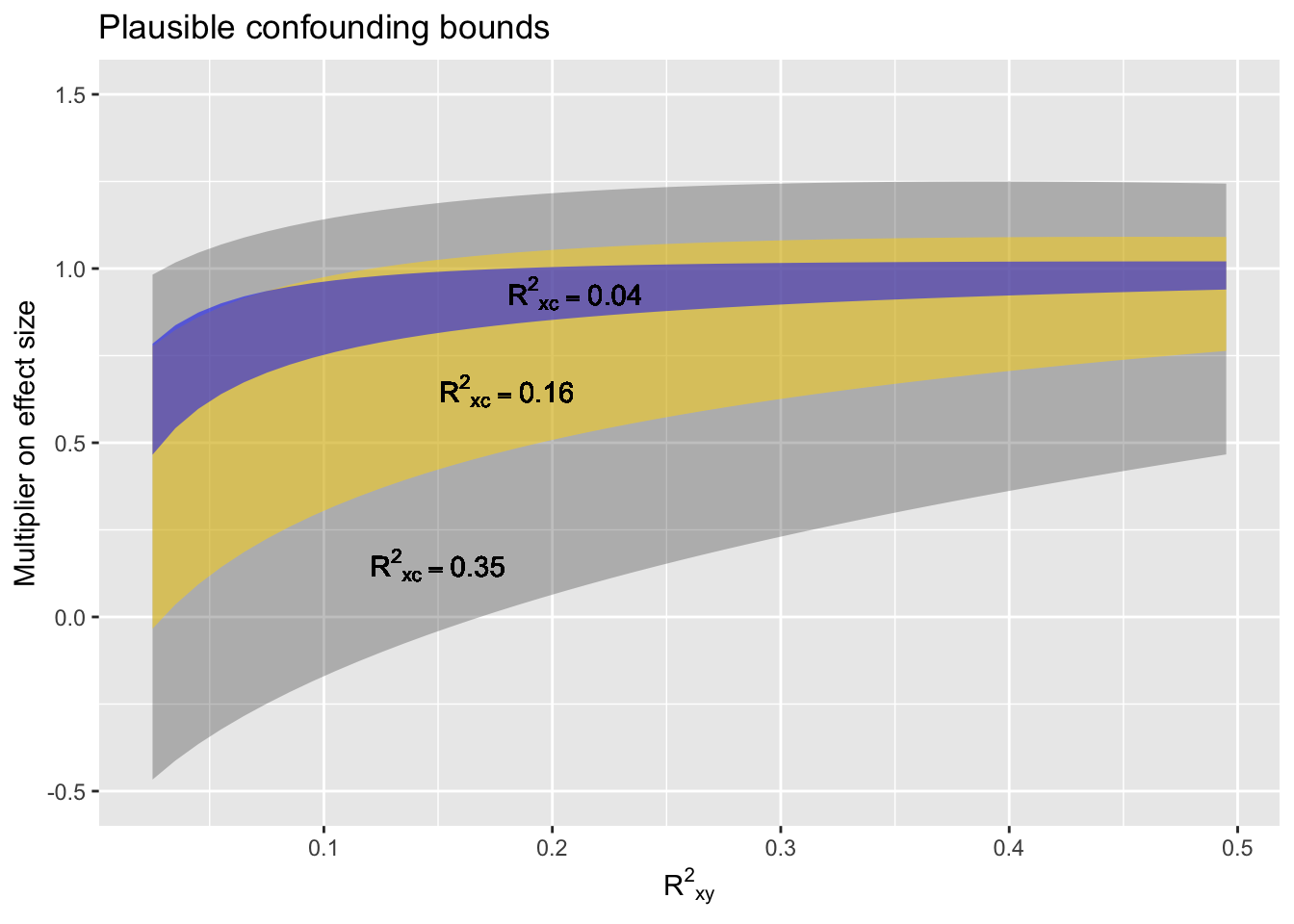

Idea of confounding interval … Accept that there might be confounding along the lines of the diagrams above.

# A proposed policy

# A proposed policy

- Did a perfect experiment? No need for plausible confounding bounds.

- Did a real experiment? Use weak plausible confounding bounds.

- Know a lot about the system you’re observing and confident that the significant confounders have been adjusted for? Use weak plausible confounding bounds.

- Not sure what all the confounders might be, but controlled for the ones you know about? Use moderate plausible confounding bounds.

- Got some data and you want to use it to figure out the relationship between X and Y? Use strong plausible confounding bounds.